PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY EMILY SCHERER / GETTY IMAGES

Hey everybody, it’s Earth Day again. Time to kick off your shoes, stretch your toes in the warm grass and inhale the stench of a million PR firms trying desperately to capitalize off your positive impressions of the natural world.

Whether it’s computer companies promising to make their products (which are full of plastics and rare earth metals) carbon neutral within a decade, influencers lounging in ostensibly sustainable clothing or YouTube partnering with content creators to make videos about how the only habitable planet in our solar system is pretty cool actually, the evidence is abundant: Earth Day has become a marketing holiday. It’s a day to sell you stuff … or, if that’s a little too “inauthentic,” at least a day to plant the good vibes that can hopefully blossom into sales later in the year.

We are now 53 years into the history of Earth Day, and it is perhaps a bit trite at this point to still be complaining about the commercialization of a holiday that celebrates cherishing what we already have. It is no longer the early aughts, after all, and irony is as dead as the Western Black Rhinoceros. But I’m not talking about the Earth Day sales and branded merchandise that annoyed me in my 20s. I’m not even talking about marketing that is explicitly misleading or underhanded. Instead, what I realized recently — and what has really sucked the last drop of enthusiasm out of this holiday for me — is that Earth Day is about branding. It’s how companies, organizations and even governments give themselves an appealing personality as “someone” who cares and is trying to help. This is the main thing Earth Day does and it got that way not because environmentalism lost … but because it won.

Back in the 1960s, in the years before Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson organized the first day of teach-ins and protests that became Earth Day, the average American’s opinion on the environment could be best summed up as, “huh?” According to a review of public opinion on the environment from 1991, the environment wasn’t relevant enough to even appear in opinion polls until 1965. That year, Gallup found 17 percent of Americans selected “reducing pollution of air and water” as a national problem that deserved government attention, ranking it ninth out of the 10 national problems listed.

Earth Day did not change this. Instead, looking at early polling, Earth Day appears to have been more of a response to shifts that were already happening. By 1970, the year of that first event, Gallup found that the percentage of Americans who saw pollution as a serious problem for the country had already more than tripled to 53 percent — placing it as the second most important problem in the country, right behind crime.

In that way, even the first Earth Day was a little bit of a marketing event — a chance for a bunch of already like-minded Americans to demonstrate their numbers to politicians who might not have previously appreciated the movement’s growth. And it worked. The country would pass a dozen federal environmental protection acts over the next decade.

In the years since, American concern for the environment and support for change has cyclically waned and waxed. Depending on the specific questions being asked, though, the overall trend has been towards a flatline — combined with a massive shockwave of partisanship that split environmentalism along party lines starting around 1990.

But that summary masks a couple of important ways that environmentalism as a social movement really succeeded. First off, caring about the environment has become normalized to such a degree that it’s now as innocuous as “do you like puppies and kittens?” It says something that 77 percent of Americans said they personally worried about the quality of the environment at the turn of the century, and, as of March 2022, 71 percent still agreed.

There are plenty of ways Americans disagree on the environment, especially when pollsters start asking the kinds of questions about taxation and tree-hugging that trigger the knee-jerk, self-sorting response of partisan identity. But, in the big picture, we all agree nice things are nice, and most of us don’t want to go back to a time when major rivers were regularly catching fire. Even some specific policies you might expect would be controversial, aren’t. Recent polling from Gallup found 69 percent of Americans say the country should prioritize renewable energy over oil and gas, and the same percentage favor taking steps to become carbon neutral by 2050.

What’s more, over the last 50 years, these beliefs have become a lot more evenly distributed, geographically speaking, throughout the country. In a 2017 paper that used Americans’ answers to a General Social Survey question about whether the country spent too much, too little, or the right amount on protecting the environment, researchers found that pro-environment opinion had spread widely since the 1970s.

The paper compared data from the years 1973 to 1982 and 2003 to 2012 and found that every single state in the country had experienced an increase in pro-environment public opinion. That change took this country from being a place where high proportions of pro-environmental sentiment were really only found in New England, Illinois and the West Coast, to one where … if I may put this indelicately … there are dirty hippies everywhere.

And that’s good. But it’s also why Earth Day sucks.

See, here’s the thing: Nobody in the corporate world wants to brand themselves as a big supporter of something if that something is not widely — nay, even blandly — popular. And that’s what companies see in environmentalism now. They’ve even got their own surveys that tout why every firm should have an Earth Day marketing strategy. The argument gets even stronger when the ad industry focuses on the coveted demographic of young people and their as-yet-unspoken-for spending money. Apparently, 62 percent of Gen Z-ers prefer “sustainable brands” (or, anyway, brands that can be made to feel sustain-y) and 73 percent are willing to pay more for “sustainable” products, at least according to these firms. And here’s Earth Day — a ripe peach of a branding opportunity, ready to be plucked. What press officer wouldn’t jump on that harvest?

Let me be clear: It is, overall, a good thing that the values of Earth Day are now this mainstream. I’m not mad about it. But it wasn’t Earth Day that got us to that saturation point. Instead, Earth Day is just a tool for connecting people who share pro-environment beliefs and getting them to do something about it. Fifty-three years ago, that meant making a big enough political fuss that it helped inspire President Richard Nixon, of all people, to clean up the country’s air and water despite his fears that the environmental movement wanted everyone to go back to living like “a bunch of damned animals.” Today, it means you can go buy a Hyundai.

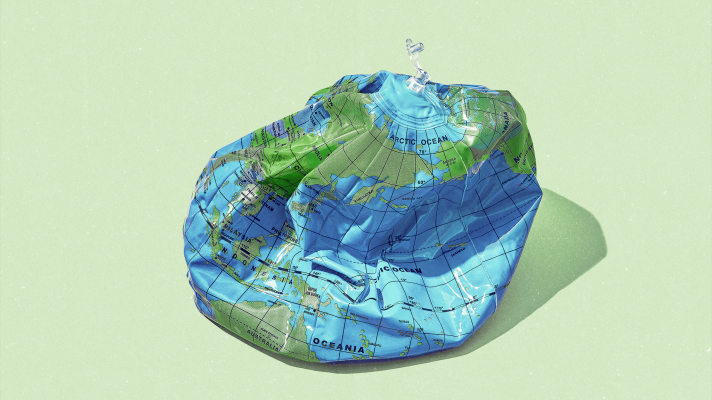

In the battle for the hearts and minds of Americans, environmentalism won. It’s just unfortunate that the prize is a swag bag.